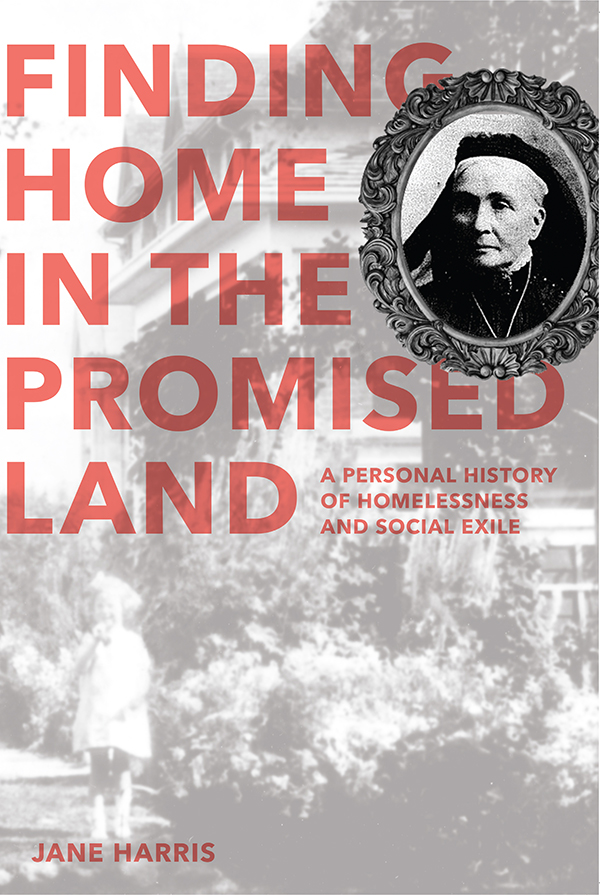

Finding Home in the Promised Land: A Personal History of Homelessness and Social Exile

Non-Fiction

PurchaseAbout the book

- Winner of the 2016 James H. Gray Award for Short Non-Fiction

Finding Home in the Promised Land is now available as an ebook from Signature Editions. The print version of this book is available from J. Gordon Shillingford Publishing: www.jgshillingford.com/shop-books

Finding Home in the Promised Land is the fruit of Jane Harris's journey through the wilderness of social exile after a violent crime left her injured and tumbling down the social ladder toward homelessnes — for the second time in her life — in 2013. Her Scottish great-great-grandmother Barbara's portrait opens the door into pre-Confederation Canada; her own story lights our journey through 21st-century Canada.

Harris asks why Canadians fell into accepting diminished dreams, and ignoring the obvious—that trauma and poverty are inextricably linked, and it is social exiles who fall through the cracks. She asks why Canada, a nation of exiles driven to create their own Promised Land, could ever accept as normal poorhouses, soup kitchens, food banks, shelters, and an ever-growing class of working poor. When did charity, another word for love, turn into cold bureaucracy?

With insight and an understanding born of first-hand experience, Harris makes complex research easy to understand. She uncovers the sad truth that the taxes and charitable gifts the prosperous among us pay as tolls to avoid looking at the poor fix nothing. Instead, they fund a poverty industry that keeps the dispossessed in a thorny exile. Once they have fallen into the cracks, the system leaves them there.

But Harris also uncovers a path out of the bureaucratic wilderness that could eliminate social exile in Canada. This is an important book for anyone interested in how the social inequities in our society can be addressed.

About the author

Jane Harris is the winner of a 2016 Alberta Literary Award, the James H. Gray Award for Short Non-Fiction, and was a finalist in the 2016 Alberta Magazine Publishers’ Association Showcase Awards for her essay, “The Unheard Patient.” Her memoir, Finding Home in the Promised Land, now out in E-Book Format through Signature Editions is the second book by Jane Harris to be published by J. Gordon Shillingford Publishing. The first, Eugenics and the Firewall: Canada’s Nasty Little Secret was published in 2010. Jane has also contributed to two Canadian anthologies. Her articles about business, personal finance, history, faith, politics and social issues have appeared in more than a dozen publications including Write, Alberta Views, Winnipeg Free Press, Canadian Capital, Alberta Venture, Lethbridge Herald, and The Anglican Planet.

Excerpt

from The Promise on My Mantle

When I was six, I stood aghast at the sight of the Royal Canadian Legion Pipers, in their bearskin and kilts, marching down the street beside an overgrown park by the railway tracks in Drumheller, Alberta on Dominion Day. I was scared of soldiers, even old ones who had traded guns for shovels and cash registers, but the pipes mesmerized me. They sounded like home I could not find.

On my mantle sits a picture of an Ontario farmer's widow dressed in mourning. The framed photocopy of a picture we thought was lost (until it popped up in a history book riddled with errors and written by strangers) contains a promise, not written in words, but in my great-great-grandmother's eyes.

Before World War I, putting on a widow's veil was a life transition that warranted a trip into the city to pose in front of a professional photographer. While all widows were expected to put on a black dress for at least one year of mourning, Barbara's pricey widow's weeds mark her as an untouchable lady of rank, a woman whose mourning was expected to be a life sentence.

Although she is about half the width of the diamond queen, Barbara Gilchrist does a fine impression of Queen Victoria, right down to the black veil and starched lace collar. The wide weighty sleeves piled over her arms, pressed black ruffles burying her thin chest, and hair-filled locket hanging from the metal mourning chain on her long neck–all signs of her position as a widow with a well-funded annuity and the big events of life behind her–don't quite hide the fact that she was once a hopeful highland lass, barefoot on the deck of a creaky wooden ship, watching home fade from view; or that she still has crops to bring in, teenagers to launch, and hopes for them all.

She has high cheekbones, a narrow brow, and drooping eyelids-like mine. But her beautiful wide eyes are filled with sad discomfort-probably at being corseted and pulled beneath the weight of her costly garb as much as over the loss of the second husband who lies buried beside his first wife.

Look a little closer. Her stare belies a hope outstretching her pinching corset. Canada has turned a penniless crofter's daughter into a lady who spends her days in a dress as unsuitable for labour as any the Queen wears. The widow still dreams.

No doubt Barbara thought her own sacrifices were enough to ensure her children's children's grandchildren would never lose their home. Sadly, she was wrong. Though most of her descendants prosper, making a home in this Promised Land has never been an easy road. For some, Canada has been another place of hungry exile. And I have been among them.

I was caught in the poverty trap myself–twice. I fought my way out of that wilderness, but I still wear cuts inside my body and soul. More than that, my eyes can no longer look away from the carnage of human lives devoured, on every street and in every town, by Canada's poverty industry.

Barbara's brood and their prosperous neighbours didn't ride past Wellington Country's poorhouse everyday. It was about 20 kilometres away, on the road between Fergus and Guelph. Still, they passed it a few times a year when they took the big trip to Guelph.

Our generation is not much different. While thousands struggle to make a home in the place our ancestors insisted would be the Promised Land of prosperity, we order lattes and dessert, oblivious to the fact that the cashier can't afford lunch. We drive gas-guzzlers past homeless shelters and food banks, not just in our cities, but also in our smallest towns, without a thought about our neighbours inside.

The taxes and charitable gifts the prosperous among us pay as tolls to avoid looking at the poor fix nothing. Instead, they fund a poverty industry that keeps the dispossessed in an exile thornier than any back bush squatter's camp.

It boils down to this. Our ancestors built poorhouses and soup kitchens to keep squatters from building shanties in their pastures and woodlots. We spend millions buttressing a multi-million dollar poverty industry that keeps the poor too busy cracking stones of futility and chopping their way out of the bureaucratic frost to help us bring in the harvest.

How did this nation of exiles come to accept fist poorhouses, then soup kitchens, food banks, shelters, and a silent suffering class of working poor? How did charity, another word for love, become cold bureaucracy? Finding Home in the Promised Land: A Personal History of Homelessness and Social Exile is the fruit of my search for the answers to those questions. My great-great-grandmother Barbara's portrait opens the door into pre-Confederation Canada. My own story lights our journey through 21st-century Canada. I hope it helps us find our way home.

Reviews

“"I fought my way out of the wilderness, but I still wear cuts inside my body and soul."

In Finding Home in the Promised Land, author Jane Harris shares her deeply personal story of domestic violence, poverty, homelessness,…” >>

— Darlene O'Leary The Catalyst, Summer 2017

Back to top

Back to top