About the book

- Nominated for the Creative Nonfiction Collective Readers' Choice Award

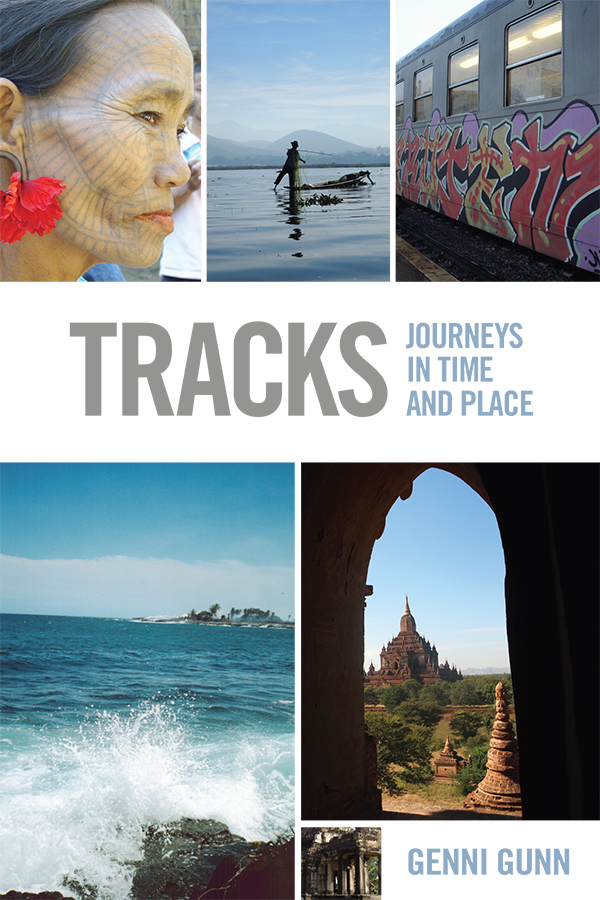

Tracks is a compilation of personal travel essays that range across three continents, from Italy, where Genni Gunn was born and spent her early years, to Canada and Mexico, and through Asia, where she has travelled many times, both reconnecting with her sister and witnessing the emergence of new political realities in Myanmar. While these are journeys into the new and unknown, they also trigger the inner journey to the realm of memory. These pieces dig deep into personal territory, exploring the family ties of an unusually peripatetic family.

In the 1950s, Gunn’s parents travelled within Italy, settling wherever Gunn’s father’s work took him. Their two young daughters were sent to live with relatives, Genni in southern Italy, her sister Ileana in northern Italy. The family was eventually reunited in Canada. Gunn’s father was a mysterious presence — much later she learned he was working with British Intelligence, but during her childhood all she knew was that he would disappear as suddenly as he had appeared. Indelibly marked by their unusual childhood, the sisters became wanderers themselves. While in some ways, their world shrank with the departure of their parents, in other ways, their imaginations were opened to new possibilities. Gunn explores some of those possibilities in this collection. An inveterate traveller, she questions the impulse behind the need to stay in motion, to always be the “other” in the world, while always seeking the home that never was.

About the author

Genni Gunn is an author, musician and translator. Born in Trieste, she came to Canada as a child. She has published twelve books: three novels -- Solitaria (longlisted for the Giller Prize 2011), Tracing Iris (made into a film, The Riverbank), and Thrice Upon a Time (finalist for the Commonwealth Writers' Prize); three short story collections -- Permanent Tourists, Hungers and On the Road; three poetry collections -- Faceless, Mating in Captivity (finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award), and Accidents; and a collection of personal essays, TRACKS: Journeys in Time and Place. As well, she has translated from Italian three collections of poems by two renowned Italian authors: Devour Me Too (finalist for the John Glassco Translation Prize) and Traveling in the Gait of a Fox (finalist for the Premio Internazionale Diego Valeri for Literary Translation) by Dacia Maraini, and Text Me by Corrado Calabrò. Two of Gunn’s books have been translated into Italian and Dutch.

As well as books, she has written an opera libretto, Alternate Visions, produced by Chants Libres in 2007 (music by John Oliver), and projected in a simulcast at The Western Front in Vancouver; her poem, "Hot Summer Nights" has been turned into classical vocal music by John Oliver, and performed internationally. Before she turned to writing full-time, Gunn toured Canada extensively with a variety of bands (bass guitar, piano and vocals). Since then, she has performed at hundreds of readings and writers’ festivals. Gunn has a B.F.A. and an M.F.A. from the University of British Columbia. She lives in Vancouver.

Excerpt

from Terra Incognita

Trust is a tentative and intrinsically fragile response to our ignorance… — Diego Gambetta

“It’s almost dark,” the agent says, furrowing his eyebrows. He wears a black leather jacket and a dark-blue, patterned longyi. On his feet, blue rubber flip-flops. In the twilight, his black-rimmed glasses reflect the mountains which hover behind us in various shades of midnight blue silhouettes against sky. He slides open the door of the minivan, and Ileana, Peter, Frank and I step in. Then the agent hands us our passports and tickets, and pats the passenger door, as if it were a water buffalo. “Have a good trip,” he says. “I’ll meet you here in a few days.” He raises his arm, waves, then turns and walks away.

It’s December 2007, and in the past week, we have seen only a handful of foreigners — German, Italian, French — no one from North America, possibly due to the travel advisories which recommend against non-essential travel, warn travellers to avoid large gatherings, and point out that freedom of speech and political activity are not permitted here, evidenced in September of this year, when the pro-democracy march led by the monks ended in a brutal crackdown by the military.

In Yangon, at the height of the protests, roads swelled with over 100,000 people forming a cordon around the marching monks, despite the warnings to disperse, in a country where no more than five people can legally gather. Simon told us that trucks full of thugs — some dressed as monks — were stationed on street corners, positioned there to infiltrate the crowd and cause disturbances. Riot police advanced in solid lines, batons banging on metal shields. The crowd armed itself with bricks, no match for tear gas, rubber bullets and live rounds. From the tops of buildings, platoons of armed soldiers pointed guns down into the street. While monks sat and prayed in the shadow of the Shwedagon pagoda, pleading for peace and calm, riot police armed with batons, rifles and bayonets plowed through the crowd, beating dissenters. Some monks tried to flee over walls and were shot. Clashes broke out all over the city. Army units advanced in threatening lines. Soldiers beat and arrested civilians. An estimated 15,000 police and riot troops were on the streets. The government admitted to killing ten people, including a Japanese photographer, whose execution-style murder recorded on a cell phone and broadcast across the world became a contemporary iconic symbol of this government’s oppression. According to Al Jazeera, observers said that far more died, but it is impossible to know how many. Thousands of people were arrested during night raids. By the following month, of the 75,000 monks who live in Yangon, few were visible in the streets. “We don’t have the strength,” one said. “We don’t have the weapons. We don’t have the freedom.”

The minivan pulls out, and we settle back. I’m tense and aware, everything open, everything unfamiliar — the country, the minivan, the two men who speak no English, our destination. We have no way of communicating with anyone outside this minivan, this country, this moment. No cell phones, no internet, no information beyond an itinerary which lists our travel dates. A surrender to trust — something we’re not used to back home. In his essay “Can We Trust Trust?” from Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, social scientist Diego Gambetta claims that trust and uncertainty are codependent. “For trust to be relevant,” he says, “there must be the possibility of exit, betrayal, [and] defection.” Yet at home, the very possibility of this uncertainty would keep us from climbing into a vehicle with strangers and heading into the unknown. Here, in a country where knowing who to trust is an ambiguous proposition, we are doing just that. If we disappeared tomorrow, who would know? We are easy targets for thieves, carrying kyat — no traveller’s cheques can be cashed here — and some US currency, although it is illegal for nationals to own it, and hard for them to exchange it unless they have connections, though what exactly constitutes connections, we don’t know — a murky territory, without a clear distinction between rulers and ruled. A taxi driver might make a disparaging comment about the junta, then moments later, mention his son is a soldier. We don’t stay in government hotels on principle, unwilling to support them, then discover that without government approval, one can’t open a hotel. It’s all ambiguous, and we are careful with our words.

We planned to undertake this part of the trip in daylight, so we could see the scenery, the climb to the lake. However, our plane has been delayed three hours — no flights in or out — to allow the generals to travel unhindered around the country, their boots pounding red carpets in this yearly expedition of feigned goodwill and devotion, to temples and gilded stupas, as if their presence could deceive the Buddha, as if they could gold-foil their way into paradise, while here on earth, their entourages rage state to state, furrowing a trail of fear and misery and death. No one speaks of torture, no front-page exposés, though this year alone, over 900 political dissidents have been locked up in Insein Prison. No world outrage at this insanity. Only silence.

We are in Shan State, headed to Inle, Myanmar’s second-largest natural lake. Eight hundred and seventy-five metres above sea level, twenty-two kilometres long, and eleven wide, it is surrounded by high misty blue hills, silk-screened against the horizon. The road is narrow, a one-lane strip, potholed, gravelled, with jagged edges and sheer drops. A fog descends. We travel slowly, quietly, staring out.

In the few weeks before we came, I had read what I could about this country: books and articles of ethnic struggles, bloody history, detailed monstrosities perpetrated by the government upon its people, brilliant political essays in glossy magazines, mediocre web pages of travel agencies, government offices and travellers’ blogs. All this seems both inadequate and distant now that we’re here, in the semi-dark, faltering on the brim of cliffs, around hairpin curves and switchbacks, the mountainside exotic danger, terra incognita. We yield to transport trucks — pre-WWII — to rusted cabs and hooked-nose hoods, to blinding beams in the dismal tracks of tires; swing to one side, manoeuvring past inch by inch, as if in a slow choreographed pas de deux, and snake through the obsidian night, our blinded selves awakened to a trance. We don’t speak, the air itself charged, and I recall another night, another journey, in Canada this time, on a May 24th long weekend, when on a whim, Frank and I decided to drive to the Interior, almost five hours away.

We left in late afternoon, drove up past Hope, up the Coquihalla Highway with its game fencing to keep wildlife out or maybe us in. In Merritt, with the sun low in the sky, we searched for accommodation among the No Vacancy signs.

“It’s a long weekend,” one motel clerk said, frowning. “Everything’s been booked for months.” She looked at us and softened. “Give me a minute. I’ll make a few calls and see if there’s anything available.”

We waited in the car. Here and there, clumps of sagebrush huddled in the bare dusty ground. “We could always drive on to Kelowna or Penticton,” Frank said, optimistically.

Presently, the clerk came out and handed us an envelope, on which she’d scribbled directions to a horseback riding ranch about an hour away. “Good luck,” she said, rather ominously, I thought. We debated whether to search for a restaurant. It was now close to 8:30, and we were both hungry.

“There’ll be food at the ranch,” I said. “I’d rather get there while it’s light out.” I stared at the envelope. The pencilled directions had us driving for an hour or so to Elkart Road exit, onto a gravel road until we reached a T, then left towards the ranch.

We reached the exit in twilight. We had climbed a steep hill and were now at the top, in the middle of a dense, dark forest. I shivered, and Frank turned up the heat. We hadn’t seen a house since we’d left Merritt. The gravel road was rough, as though it hadn’t been graded this year. After fifteen minutes more, we came to the T, and found a crude, hand-made wooden sign leaning against a post: “Paradise Lake →,” arrow pointing to the right.

“Let’s turn right,” Frank said. “Paradise sounds a lot better than a horseback riding ranch.”

Paradise, yes. I turned right.

In the gathering dusk, we drove for a few kilometres, trying to avoid potholes. Parts of the road were washed away. At one point, we had to skirt a large rock. My hands tightened around the steering wheel. “What if that sign was put there by some thieves?” I said. “What if we’re murdered? How do we know there’s even a lake here? And why didn’t that woman at the motel tell us about it?”

“There’s nothing to worry about,” Frank said, Zen-like. “You’ll see. At the end of this road, we’ll come to a magnificent cedar lodge overlooking a pristine lake, the blue of which you never knew existed.”

“Sure,” I said, trying to keep it light, “or there could be a couple of guys with guns, who will take our car, and if we’re lucky, leave us here to die of exposure.”

We drove and drove for what seemed like forever, slowly over the uneven ground, the night fallen now, our headlights the only guides. I think of all this, here in Myanmar, half a world away, my stomach clenching, wondering where we are, and why this need to search out the unknown.

And soon, in the shafts of headlights, we glimpse a man here, a woman there, elusive, feet bare, longyis knotted at the waist. Some walk, some ride bicycles or trishaws. Ethereal apparitions, coming and going, emerge and fade in the dense dark. Workers returning to their homes after a day in the fields, though we see no lights, no houses, no villages. Most of the country has no electricity, or if it does, it’s sporadic, eccentric.

The minivan manoeuvres past villagers, around them, or they manoeuvre around us — all in eerie silence. At times, there are so many, it seems inevitable that we will hit someone, but this never happens. As well as pedestrians, bicycles and trishaws, carts drawn by water buffalo suddenly appear out of the mist in the beam of our lights, either in front of us or coming towards us. And still the driver steers the minivan in and out of this human traffic, in a fluid trance-like motion. A step into another century; crepuscular ghosts dissolving into shadows at the edge of the road.

We thread through darkness for an hour and a half, across a valley twenty-two kilometres long, in the umbrage of mountains, phantoms and banyans scaffolding the sky. None of us speak, as though hypnotized. Then scattered lights. Smoke tinges the air. A village on the lake shore. Dust trails us into Nyaung Shwe, where the streets are deserted, and cooking fires flicker between the wooden slats of thatched huts. Here and there, a generator signals a guesthouse or hotel for foreigners like us.

In front of a crumbling façade, the driver hauls out our luggage, and motions for us to follow, past the darkened building, the peeling paint, the teak colonial door. The night is cool, but our jackets are in the luggage. It seems incredible that only hours ago we were sweltering in the humid 38°C of Yangon.

Two men spring from the shadows, gather our bags and flip-flop around the building. We follow, shivering, our sandals hollow on the wooden planks, until a bare bulb at the rear haloes the shallow draft, the pointed prow — a flat-bottomed boat against a makeshift wharf. The boatmen toss our bags into the skiff, cage them beneath a net as if they might escape. Inside the boat, four wooden chairs await, each with seat cushion and life jacket. Our driver gestures us into the chairs, nodding, his Myanma words soft and encouraging.

The boat sways madly with every footfall. Waves slap wood. When we are settled in, our driver smiles, then turns and walks into the dark.

The boatmen squatting at stern and bow push us off the wharf. The bulb shuts off. Such darkness. The only sound is the splash of oars, the sweep of ironwood, our own elated breaths. And soon our pupils widen to contain the narrow channel cut between mist and tall silhouettes of homes on stilts, night flowing beneath them.

The motor sputters into motion. We skim black water, black night, only the sky a brilliant 3-D tapestry. Now and then, another engine grumbles. Our boatman flicks a flashlight once, twice, three times, catches the eerie shape of a boat ahead or to the side of us. I wonder how we manage not to collide. No one speaks. The air is cold on our bare arms, our thin T-shirts. I carefully pull the life jacket from the back of my seat and use it as a shield against the wind.

I could talk about our destination, the flicker of lights in the distance, the stilt Paradise Hotel in the middle of the lake — the thatched-roof huts connected by a boardwalk; our three days here; the pale-blue, plate-glass lake at 6:00 a.m.; the elephant-grass mats staked into rows in the middle of the lake, bobbing with vegetables, flowers; the magenta hyacinth blossoms drifting languidly in the swishing waves; the floating islands of sugar cane wafting in sun; the woman singing in her house; the narrow waterways between rows of tomato plants; the floating markets of jade, tin, iron, silver; the scent of lavender; the crooked fingers of mountains falling into the lake; the famed Intha leg-rowing fishermen, their cone-shaped nets; the various villages around the lake — these water people: the lotus weavers of Inpawkhon, rhythmic, to the sound of clack, clack, clack; the five blacksmiths of Selkowouen pounding mallets against red hot metal, while an old man fans the fire with chicken feathers; the girls of Nanpan village rolling cheroots below clear plastic bags of water hanging from the rafters to fool mosquitoes or flies into seeing insects larger than themselves; the delicate women in traditional silk or cotton dress — long fitted skirts and tops with modest three-quarter sleeves, rowing boats laden with rice bags, sitting cross-legged, separating threads of lotus, tending the floating gardens; the Phaung Daw Oo pagoda monastery, home to the five miraculous Buddha heads; the Padaung women wearing neck rings which crush and deform their shoulder bones; Ywama, the largest floating village on the lake — a tropical Venice with its web of canals connecting boardwalks and bridges, splendid teak houses atop large wooden pylons driven into the lake bed; the potted orchids hanging from window-sills; flat boats everywhere: bulging with monks in brick-red robes, laden with fertile mud dredged from the bottom of the lake, brimming with bamboo poles; Indein Creek, which twists and turns under wooden bridges, cuts through sugar cane plantations and rice paddies, its clay banks reinforced with sticks; villagers ploughing, harrowing behind water buffalo, carrying hoes, scythes and baskets; the dirt path past market stalls, past circles of men squatting, up to the ancient stupas, trees growing out of their sides, roots clawing their walls; the small boy who kept us from stepping on poisonous snakes; and back on the lake, the flocks of whistling ducks, the white egrets, the dozens of species of birds, jacanas; floating villages, water people, water.

But what I most recall from this journey comes before all this. We’re back in that shallow draft at night, skimming the narrow channel. Suddenly, the sides fall away, and we’re out in the lake, travelling swiftly in total darkness, under a dazzling sky. Mist swirls in the air. Here and there, dark clumps of vegetation hover in front of us, beside us, in hazy sculptures the boatmen skirt around. I am thrilled by this remoteness, this total loss of anything familiar, this growing sense of singleness, everything new, all that I know falling away second by second, so that I am simply experiencing the moment, without expectations, abandoned to the mystery unfolding. I wonder if this is how the early explorers felt, their hearts fluttering, their eyes and ears open to the unknown. And as we progress — across the water in the black, black night, I also think about Conrad, and Heart of Darkness, and how this journey is a literal journey into darkness, but I have no foreboding, no fear. I am exhilarated by the wind, by the spray of water at our sides, by the brilliant sky and by the darkness itself, which envelops me, ushering me forward.

From Genni Gunn

Reviews

“There are many sorts of tracks: animal tracks, railroad tracks, race tracks, music tracks. Tracks also can be a verb, and in this new book, Canadian novelist Genni Gunn tracks herself through a series of travel essays in which places…” >>

— Linda Knowles CanText

“Good travel writing opens up the mind, even as it relates a journey. Genni Gunn seems to know this intuitively.

And though her collected essays aren't all, or even exclusively, about travel, her instincts remain sound throughout.

— Doug Johnston Winnipeg Free Press

“Gunn’s writing is exquisite and beautifully rendered. She transports the reader to foreign lands by rooting her language in the senses – visual, auditory, tactile. It is this which transforms her narrative into an emotional journey through time and space.” >>

— Wendy Caribousmom

“Well-written and keenly observed, these essays move back and forth between a conviction that wanderlust is the author’s true home — superior to “the claustrophobia of continuity” — and a longing to penetrate the mystery of her relationship to her…” >>

— Carole Giangrande, author

“In Tracks: Journeys in Time and Place, Genni Gunn offers a wonderful smorgasbord of memoir, travelogue and biography which includes travel and family photographs as well as competing and inviting crostoli recipes from her mother and aunt. It is hard…” >>

— Carol Matthews Event

Video

From the Road to the Writing Desk: Travel in Writing - Virtual Event

Genni Gunn, Linda Kenyon, and Denise Roig talk about how their travels influence their writing.

Back to top

Back to top